Inspirados já nos ensinamentos de Sófocles, aqui, procurar-se-á a conexão, pelo conhecimento, entre o velho e o novo, com seus conflitos. As pistas perseguidas, de modos específicos, continuarão a ser aquelas pavimentadas pelo grego do período clássico (séculos VI e V a.C).

sexta-feira, 9 de abril de 2021

O Antagonista não tem medo

Quem luta contra nós reforça os nossos nervos e aguça as nossas habilidades. O nosso antagonista é quem mais nos ajuda.

- Edmund Burke

***

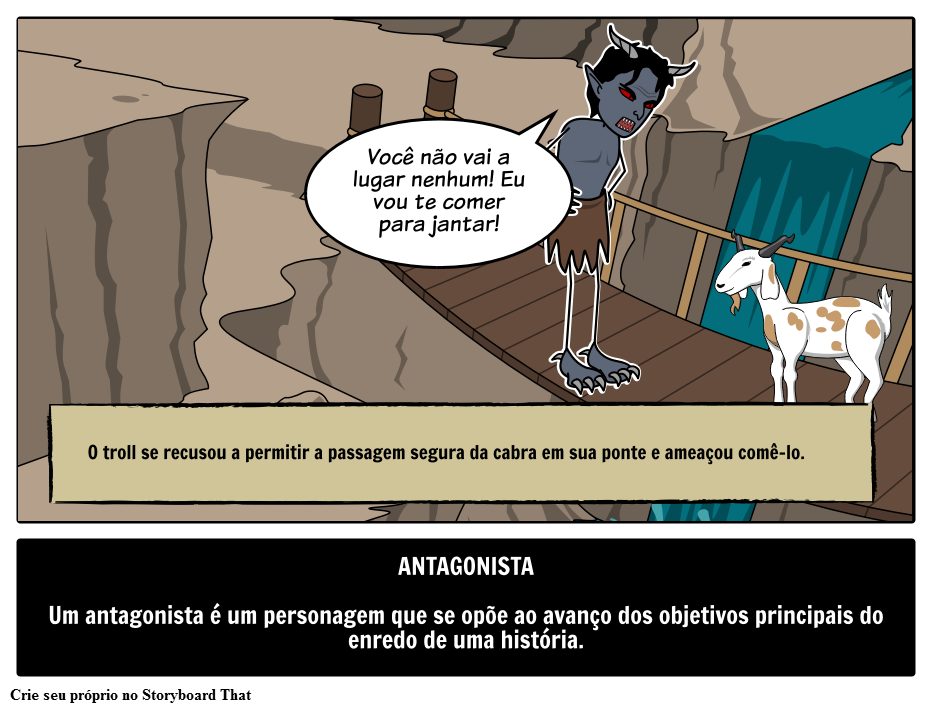

Algo ou alguém que tenta acabar com o protagonista, impedindo que ele alcance seus objetivos.

***

***

O Antagonista não tem medo

Foto: Adriano Machado/Crusoé

***

Logo depois que O Antagonista foi lançado, em 2015, aconteceu algo inédito comigo: passei a ser cumprimentado na rua, em restaurante e até em avião. O mesmo começou a ocorrer com os demais jornalistas que foram se agregando ao site. Elogiavam a nossa coragem e disposição para denunciar os crimes cometidos pelo PT. Incomodado com o nosso alcance, e cada vez mais implicado na Lava Jato, Lula tentou emplacar a mentira de que os jornalistas deste site integravam uma “associação criminosa”. Até para a polícia o seu advogado, agora homenageado por ministro do STF com lágrimas nos olhos, quis me levar.

Veio o impeachment de Dilma Rousseff, a Lava Jato ganhou mais impulso, Lula foi preso, lançamos a Crusoé e continuamos a ser cumprimentados, mas menos. Previsivelmente, os primeiros ataques extrapetistas iniciaram-se quando os irmãos Batista entregaram Michel Temer e a Lava Jato passou a investigar tucanos. Ganhou força a calúnia inventada ainda sob o PT de que o site “especulava com a notícia”, alusão ao fato de termos como sócios na época uma empresa de relatórios financeiros.

Na campanha presidencial de 2018, enquanto boa parte da imprensa se dedicava a deslegitimar a candidatura de Jair Bolsonaro, nós pegamos essa contramão para afirmar que, por mais que o homem fosse quem fosse, ele tinha o direito de ser candidato. Do outro lado, afinal de contas, havia um ladrão. Ressuscitados pela candidatura do poste de Lula, os petistas aumentaram o volume da difamação nos blogs sujos criados e patrocinados por eles: a nossa posição sobre o candidato Bolsonaro era mais uma prova de que não passávamos de um “site de extrema direita”. O sujeito foi eleito, tentamos entender o bicho novo que se instalara no Planalto, dando crédito ao voto de 57 milhões de brasileiros, mas o abafamento das denúncias contra Flávio Bolsonaro não demorou a ser o principal plano de governo, o que acabaria levando à saída de Sergio Moro do Ministério da Justiça. Para não falar da agenda aloprada do que se convencionou chamar de ala ideológica. Seria no mínimo irresponsável não tocar mais de um dedo nessas feridas.

Como O Antagonista continuou a fazer o trabalho a que se propôs desde o início — o de fiscalizar o poder, de maneira independente (recusamos todo tipo de propaganda governamental) –, viramos alvo dos bolsonaristas (e do STF, no episódio da censura por causa da reportagem da Crusoé sobre “o amigo do amigo de meu pai”, mas essa é outra história). Eles, os bolsonaristas, não só retomaram a calúnia petista, como passaram a nos associar à figura do governador tucano João Doria, fingindo ignorar que o governador paulista apanha bastante no site. Dia sim, outro idem, a rede de ódio bolsonarista mente que recebemos dinheiro de Doria, enquanto aplaude a sociopatia e o amadorismo do seu líder em relação à pandemia. A batatada da vez é essa do “Mamata Connection”. Paralelamente aos ataques bolsonaristas, os petistas associados a tucanos e demais fisiológicos conseguiram minar a Lava Jato com as mensagens roubadas — e, com elas, buscaram reconstruir a falsa história de que éramos uma espécie de braço armado dos procuradores e de Sergio Moro. Os bolsonaristas também entraram nesse vácuo. A lorota dos cúmplices de hackers desmoronou logo.

Não sou — não somos — mais cumprimentados na rua (quando havia rua). Nenhum problema, porque jamais tive qualquer ilusão sobre esse tipo de fama e as minhas vaidades passam longe desse tipo de agrado. Espero que os meus colegas compartilhem de atitude semelhante perante a vida. Quando vez por outra ainda era abordado e me perguntavam por que havíamos mudado, respondia que permanecíamos — e permanecemos — no mesmo lugar: do lado do Brasil, não de partidos, organizações criminosas ou aspirantes a caudilhos. Parece simples, deveria ser simples, mas não é para muita gente. Pena.

Com a soltura de Lula, a sanha dos blogs sujos e dos militantes virtuais petistas (essa gente bacana que quer se vender como “polo democrático”) vai se juntar à das vozes compradas pelo bolsonarismo e da milícia digital capitaneada pelo gabinete do ódio. Estamos prontos para o que der e vier. Não há bravata ou heroísmo nisso. Apenas dever de ofício. Enquanto contarmos com o apoio dos cidadãos silenciosos que a tudo assistem entre incrédulos e indignados, iremos em frente. São eles que, quando a coisa fica feia além da conta, tomam as avenidas para exigir mudanças de verdade.

Por Mario Sabino

05.04.21 11:18

*** ***

https://www.oantagonista.com/opiniao/o-antagonista-nao-tem-medo/

*** ***

***

***

Há 27 anos no ar, ‘Manhattan Connection’ sai da GloboNews

*** ***

https://istoe.com.br/ha-27-anos-no-ar-manhattan-connection-sai-da-globo/

*** ***

***

Manhattan Connection | Marta Suplicy, Paulo Rabello de Castro e Preto Zezé

***

TV Cultura

O Manhattan Connection desta quarta-feira (7/4) conta com a participação de Marta Suplicy, secretária de Relações Internacionais da cidade de São Paulo, do economista Paulo Rabello de Castro e de Preto Zezé, presidente da Cufa (Central Única das favelas). Apresentado por Lucas Mendes, Pedro Andrade, Caio Blinder, Diogo Mainardi e Angélica Vieira

*** ***

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SQDjQD6l8II

*** ***

***

Literatura

O que é e qual a diferença entre protagonista e antagonista

Escrito por Débora SilvaEm 17/10/2017 (atualização: 14/11/2018)

Uma narrativa requer uma série de elementos, incluindo os personagens, que podem ser classificados quanto à importância e quanto à existência.

Os tipos de personagens estão presentes na literatura, no cinema, teatro, televisão etc., e incluem o protagonista e o antagonista, considerados fundamentais na maioria dos fatos.

Diferença entre protagonista e antagonista

O protagonista e o antagonista são antônimos na linguagem literária e nos mais variados gêneros onde podemos encontrar personagens. O primeiro é o personagem principal de uma narrativa, em torno do qual a história é desenvolvida; o segundo se contrapõe ao protagonista, mas nem sempre está presente nos enredos.

Protagonista

O protagonista é um herói (ou anti-herói) e, em alguns casos, é possível encontrar mais personagens desse tipo. Alguns exemplos de protagonistas são: Nino, do Castelo Rá-Tim-Bum e Carly Shay, das séries iCarly.

***

***

Esses personagens desempenham papéis como mocinho e vilão na maioria das narrativas

O antagonista se opõe ao protagonista, por isso nem sempre ele é o vilão (Foto: depositphotos)

***

Antagonista

O antagonista geralmente é o vilão da história e também se destaca na obra, mas nem sempre é um ser humano, mas algo que dificulta os objetivos do protagonista, como um objeto, animal, monstro, circunstância, uma força na natureza, uma instituição, um espírito, entre outros. Alguns exemplos de antagonistas são: Coringa, de Batman; Scar, de Rei Leão e Posidão, de Odisseia. É importante ressaltar que nem sempre o antagonista é o vilão, pois, no caso do protagonista ser um anti-herói, os antagonistas podem ser os heróis.

Trama

O protagonista e o antagonista aparecem juntos no decorrer da narrativa, já que o segundo impede que o primeiro alcance os seus objetivos. Em grande parte das histórias que lemos ou assistimos, é possível identificarmos as forças do bem e do mal, em que os personagens desempenham papéis como mocinho e vilão, representando o protagonismo e o antagonismo, respectivamente.

O dicionário Michaelis define protagonista como “1. No antigo teatro grego, o principal ator de uma peça. 2. O principal personagem de um filme, de uma obra literária, uma peça, uma telenovela etc., em torno do qual a ação se desenrola. 3. Participante ativo ou de destaque em um acontecimento.”

O mesmo dicionário define antagonista como “que ou aquele que é e age contrário ou em sentido oposto a alguém ou alguma coisa; adversário; opositor.”

Sobre o autor

Débora Silva

Formada em Letras (Licenciatura em Língua Portuguesa e suas Literaturas) pela Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei (UFSJ), com certificado DELE (Diploma de Español como Lengua Extranjera), outorgado pelo Instituto Cervantes. Produz conteúdo web, abrangendo diversos temas, e realiza trabalhos de tradução e versão em Português-Espanhol.

*** ***

https://www.estudopratico.com.br/o-que-e-e-qual-a-diferenca-entre-protagonista-e-antagonista/

*** ***

***

***

Edmund Burke e o conservadorismo - Brasil Escola

***

Confira a nossa aula para entender melhor a filosofia de Edmund Burke. Já ouviu a frase “Eu sou liberal na economia e conservador nos costumes”? Ela tomou espaço entre as pessoas nos debates políticos dos últimos anos, mas é utilizada de maneira desvirtuada de seu sentido original. O filósofo irlandês Edmundo Burke considerava-se um liberal e, ao mesmo tempo, um conservador. No entanto, faz-se necessário entender o que foi o conservadorismo que tomou grande dos estudos deixados por Burke para a posteridade.

Brasil Escola

*** ***

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=

*** ***

***

O Pasquim

***

***

Periodicidade semanal

Formato tabloide

Sede Rio de Janeiro

Fundação 1969

Fundador(es) Jaguar, Tarso de Castro, Sérgio Cabral, Ziraldo

Término de publicação 1991

***

https://pt.wikipedia.org/wiki/O_Pasquim

***

***

***

Documentário - "O Pasquim - A Subversão do Humor" Direção e Edição: Roberto Stefanelli

***

O Pasquim - A Subversão do Humor

Em 1969, ano particularmente duro no regime militar, surgiu no Rio de Janeiro "O Pasquim", tablóide que, com sua irreverência, humor e anarquia, daria uma nova roupagem e linguagem ao jornalismo brasileiro, uma forma mais coloquial à publicidade e causaria um forte abalo nos níveis da hipocrisia nacional.

"O Pasquim - a Subversão do Humor", através dos principais personagens desta história, como ele invadiu o Brasil, enfrentando a censura e a cadeia com o riso aberto, como se fosse mais uma das farras da turma de Ipanema.

Em O Pasquim, Jaguar, Ziraldo, Sérgio Cabral, Luiz Carlos Maciel, Marta Alencar, Miguel Paiva, Claudius, Sérgio Augusto, Reinaldo, Hubert lembram como se escreveu esta página da nossa história e Angeli, Chico Caruso, Washington Olivetto e Zélio como ela foi determinante para as páginas seguintes.

Ninguém ficou rico com a publicação, embora ela tenha vendido nos seus melhores tempos, entre 1969 e 1973, até 250 mil exemplares. Um volume acima do razoável, se lembrarmos que os jornais de tiragem nacional rodam hoje, mais de 30 anos depois, com toda a informatização, a facilidade de distribuição e as fortes campanhas de assinantes, cerca de 300 mil exemplares.

A verdade é que o comportamento da chamada Patota do Pasquim era tão anárquico quanto o conteúdo do jornal. E o que ganharam gastaram entre prisão, brigas, festas e altas dosagens etílicas. Bem que os militares e a elite brasileira tentaram sufocá-lo diversas vezes e de formas variadas mas, quando conseguiram, ele já havia disseminado uma nova forma de comportamento nos meios de comunicação. Como diz Jaguar, a imprensa tirou o paletó e a gravata, ou, como diz Olivetto, passamos a escrever e nos comunicar com língua de gente, do povo.

Ficha Técnica

Direção e Edição: Roberto Stefanelli

Edição e Pós-Produção: Joelson Maia

Abertura e Videografismo: Wagner Maia

Fotografia: André Carvalheira e Edson Cordeiro

Assistente: Jorge Matos

Pesquisa, Roteiro e Entrevistas: Roberto Stefanelli

Produção: Roberto Stefanelli, Karina Staveland, Guilianno Baeta, Ana Tereza Constantino e André Bessa Maia

Narração: Luiz Carlos Linhares

Direção de Cenas: André Carvalheira

Duração: 45 minutos

Música neste vídeo

Saiba mais

Ouça músicas sem anúncios com o YouTube Premium

Música

Apesar De Você

Artista

Chico Buarque, MPB4, Quarteto Em Cy

Licenciado para o YouTube por

UMG (em nome de Universal Music Ltda.); LatinAutor, LatinAutorPerf, SODRAC, UNIAO BRASILEIRA DE EDITORAS DE MUSICA - UBEM e 7 associações de direitos musicais

Música

Soy Loco Por Tí, América-7468

Artista

Caetano Veloso

Álbum

Caetano Veloso

Licenciado para o YouTube por

UMG, AdRev for Rights Holder; LatinAutorPerf, SODRAC, LatinAutor, LatinAutor - Warner Chappell, BMI - Broadcast Music Inc., Audiam (Publishing), Warner Chappell, UNIAO BRASILEIRA DE EDITORAS DE MUSICA - UBEM e 6 associações de direitos musicais

Música

Charles, Anjo 45

Artista

Caetano Veloso, Jorge Ben

Compositores

Jorge Ben

Licenciado para o YouTube por

UMG (em nome de Universal Music Ltda.); BMI - Broadcast Music Inc., Warner Chappell, LatinAutor - Warner Chappell, LatinAutorPerf, UNIAO BRASILEIRA DE EDITORAS DE MUSICA - UBEM e 2 associações de direitos musicais

*** ***

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=113ICRQ2I9g

*** ***

***

AO VIVO: DANILO PRESIDENTE? - Papo Antagonista com Claudio Dantas e Danilo Gentili

08.04.21 17:43

AO VIVO: DANILO PRESIDENTE? – Papo Antagonista com Claudio Dantas e Danilo Gentili

***

Arte: Joelto Mata

***

***

No Papo Antagonista desta quinta-feira, Claudio Dantas entrevista o apresentador Danilo Gentili. Vai ter Danilo em 2022? O programa ainda traz os detalhes do julgamento no STF sobre a liberação de cultos e missas em meio à pandemia de Covid.

***

***

*** ***

https://www.oantagonista.com/especial/ao-vivo-danilo-presidente-papo-antagonista-com-claudio-dantas-e-danilo-gentili/

*** ***

***

***

Edmund Burke

British philosopher and statesman

WRITTEN BY

Charles William Parkin

Fellow and Lecturer of Clare College, University of Cambridge. Author of The Moral Basis of Burke's Political Thought.

See Article History

Edmund Burke, (born January 12? [January 1, Old Style], 1729, Dublin, Ireland—died July 9, 1797, Beaconsfield, Buckinghamshire, England), British statesman, parliamentary orator, and political thinker prominent in public life from 1765 to about 1795 and important in the history of political theory. He championed conservatism in opposition to Jacobinism in Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790).

Early Life

Burke, the son of a solicitor, entered Trinity College, Dublin, in 1744 and moved to London in 1750 to begin his studies at the Middle Temple. There follows an obscure period in which Burke lost interest in his legal studies, was estranged from his father, and spent some time wandering about England and France. In 1756 he published anonymously A Vindication of Natural Society…, a satirical imitation of the style of Viscount Bolingbroke that was aimed at both the destructive criticism of revealed religion and the contemporary vogue for a “return to Nature.” A contribution to aesthetic theory, A Philosophical Enquiry into the Origin of Our Ideas of the Sublime and Beautiful, which appeared in 1757, gave him some reputation in England and was noticed abroad, among others by Denis Diderot, Immanuel Kant, and G.E. Lessing. In agreement with the publisher Robert Dodsley, Burke initiated The Annual Register as a yearly survey of world affairs; the first volume appeared in 1758 under his (unacknowledged) editorship, and he retained this connection for about 30 years.

In 1757 Burke married Jane Nugent. From this period also date his numerous literary and artistic friendships, including those with Dr. Samuel Johnson, Oliver Goldsmith, Sir Joshua Reynolds, and David Garrick.

Political Life

After an unsuccessful first venture into politics, Burke was appointed secretary in 1765 to the Marquess of Rockingham, leader of one of the Whig groups, the largely liberal faction in Parliament, and he entered the House of Commons that year. Burke remained Rockingham’s secretary until the latter’s death in 1782. Burke worked to unify the group of Whigs that had formed around Rockingham; this faction was to be the vehicle of Burke’s parliamentary career.

Burke soon took an active part in the domestic constitutional controversy of George III’s reign. The main problem during the 18th century was whether king or Parliament controlled the executive. The king was seeking to reassert a more active role for the crown—which had lost some influence in the reigns of the first two Georges—without infringing on the limitations of the royal prerogative set by the revolution settlement of 1689. Burke’s chief comment on this issue is his pamphlet “Thoughts on the Cause of the Present Discontents” (1770). He argued that George’s actions were against not the letter but the spirit of the constitution. The choice of ministers purely on personal grounds was favouritism; public approbation by the people through Parliament should determine their selection. This pamphlet includes Burke’s famous, and new, justification of party, defined as a body of men united on public principle, which could act as a constitutional link between king and Parliament, providing consistency and strength in administration, or principled criticism in opposition.

In 1774 Burke was elected a member of Parliament for Bristol, then the second city of the kingdom and an open constituency requiring a genuine election contest. He held this seat for six years but failed to retain the confidence of his constituents. For the rest of his parliamentary career he was member for Malton, a pocket borough of Lord Rockingham’s. It was at Bristol that Burke made the well-known statement on the role of the member of Parliament. The elected member should be a representative, not a mere delegate pledged to obey undeviatingly the wishes of his constituents. The electors are capable of judging his integrity, and he should attend to their local interests; but, more importantly, he must address himself to the general good of the entire nation, acting according to his own judgment and conscience, unfettered by mandates or prior instructions from those he represents.

Burke gave only qualified support to movements for parliamentary reform; though he accepted the possibility of widening political participation, he rejected any doctrine of mere rule of numbers. Burke’s main concern, rather, was the curtailment of the crown’s powers. He made a practical attempt to reduce this influence as one of the leaders of the movement that pressed for parliamentary control of royal patronage and expenditure. When the Rockingham Whigs took office in 1782, bills were passed reducing pensions and emoluments of offices. Burke was specifically connected with an act regulating the civil list, the amount voted by Parliament for the personal and household expenses of the sovereign.

A second great issue that confronted Burke in 1765 was the quarrel with the American colonies. Britain’s imposition of the Stamp Act there in 1765, along with other measures, provoked unrest and opposition, which soon swelled into disobedience, conflict, and secession. British policy was vacillating; determination to maintain imperial control ended in coercion, repression, and unsuccessful war. Opposed to the tactics of coercion, the Rockingham group in their short administration of 1765–66 repealed the Stamp Act but asserted the imperial right to impose taxation by the Declaratory Act.

Burke’s best-known statements on this issue are two parliamentary speeches, “On American Taxation” (1774) and “On Moving His Resolutions for Conciliation with the Colonies” (1775), and “A Letter to…the Sheriffs of Bristol, on the Affairs of America” (1777). British policy, he argued, had been both imprudent and inconsistent, but above all legalistic and intransigent, in the assertion of imperial rights. Authority must be exercised with respect for the temper of those subject to it, if there was not to be collision of power and opinion. This truth was being ignored in the imperial quarrel; it was absurd to treat universal disobedience as criminal: the revolt of a whole people argued serious misgovernment. Burke made a wide historical survey of the growth of the colonies and of their present economic problems. In the place of narrow legalism he called for a more pragmatic policy on Britain’s part that would admit the claims of circumstance, utility, and moral principle in addition to those of precedent. Burke suggested that a conciliatory attitude be shown by Britain’s Parliament, along with a readiness to meet American complaints and to undertake measures that would restore the colonies’ confidence in imperial authority.

In view of the magnitude of the problem, the adequacy of Burke’s specific remedies is questionable, but the principles on which he was basing his argument were the same as those underlying his “Present Discontents”: government should ideally be a cooperative, mutually restraining relation of rulers and subjects; there must be attachment to tradition and the ways of the past, wherever possible, but, equally, recognition of the fact of change and the need to respond to it, reaffirming the values embodied in tradition under new circumstances.

Ireland was a special problem in imperial regulation. It was in strict political dependency on England and internally subject to the ascendancy of an Anglo-Irish Protestant minority that owned the bulk of the agricultural land. Roman Catholics were excluded by a penal code from political participation and public office. To these oppressions were added widespread rural poverty and a backward economic life aggravated by commercial restrictions resulting from English commercial jealousy. Burke was always concerned to ease the burdens of his native country. He consistently advocated relaxation of the economic and penal regulations, and steps toward legislative independence, at the cost of alienating his Bristol constituents and of incurring suspicions of Roman Catholicism and charges of partiality.

The remaining imperial issue, to which he devoted many years, and which he ranked as the most worthy of his labours, was that of India. The commercial activities of a chartered trading concern, the British East India Company, had created an extensive empire there. Burke in the 1760s and ’70s opposed interference by the English government in the company’s affairs as a violation of chartered rights. However, he learned a great deal about the state of the company’s government as the most active member of a select committee that was appointed in 1781 to investigate the administration of justice in India but which soon widened its field to that of a general inquiry. Burke concluded that the corrupt state of Indian government could be remedied only if the vast patronage it was bound to dispose of was in the hands neither of a company nor of the crown. He drafted the East India Bill of 1783 (of which the Whig statesman Charles James Fox was the nominal author), which proposed that India be governed by a board of independent commissioners in London. After the defeat of the bill, Burke’s indignation came to centre on Warren Hastings, governor-general of Bengal from 1772 to 1785. It was at Burke’s instigation that Hastings was impeached in 1787, and he challenged Hastings’ claim that it was impossible to apply Western standards of authority and legality to government in the East. He appealed to the concept of the Law of Nature, the moral principles rooted in the universal order of things, to which all conditions and races of men were subject.

The impeachment, which is now generally regarded as an injustice to Hastings (who was ultimately acquitted), is the most conspicuous illustration of the failings to which Burke was liable throughout his public life, including his brief periods in office as paymaster general of the forces in 1782 and 1783. His political positions were sometimes marred by gross distortions and errors of judgment. His Indian speeches fell at times into violent emotion and abuse, lacking restraint and proportion, and his parliamentary activities were at times irresponsible or factious.

The outbreak of the French Revolution in 1789 was initially greeted in England with much enthusiasm. Burke, after a brief suspension of judgment, was both hostile to it and alarmed by this favourable English reaction. He was provoked into writing his Reflections on the Revolution in France (1790) by a sermon of the Protestant dissenter Richard Price welcoming the Revolution. Burke’s deeply felt antagonism to the new movement propelled him to the plane of general political thought; it provoked a host of English replies, of which the best known is Thomas Paine’s The Rights of Man (1791–92).

In the first instance Burke discussed the actual course of the Revolution, examining the personalities, motives, and policies of its leaders. More profoundly, he attempted to analyze the fundamental ideas animating the movement and, fastening on the Revolutionary concepts of “the rights of man” and popular sovereignty, emphasized the dangers of democracy in the abstract and the mere rule of numbers when unrestrained and unguided by the responsible leadership of a hereditary aristocracy. Further, he challenged the whole rationalist and idealist temper of the movement. It was not merely that the old social order was being pulled down. He argued, further, that the moral fervour of the Revolution, and its vast speculative schemes of political reconstruction, were causing a devaluation of tradition and inherited values and a thoughtless destruction of the painfully acquired material and spiritual resources of society. Against all this, he appealed to the example and the virtues of the English constitution: its concern for continuity and unorganized growth; its respect for traditional wisdom and usage rather than speculative innovation, for prescriptive, rather than abstract, rights; its acceptance of a hierarchy of rank and property; its religious consecration of secular authority and recognition of the radical imperfection of all human contrivances.

As an analysis and prediction of the course of the Revolution, Burke’s French writings, though frequently intemperate and uncontrolled, were in some ways strikingly acute; but his lack of sympathy with its positive ideals concealed from him its more fruitful and permanent potentialities. It is for the criticism and affirmation of fundamental political attitudes that the Reflections and An Appeal from the New to the Old Whigs (1791) retain their freshness, relevance, and force.

Burke opposed the French Revolution to the end of his life, demanding war against the new state and gaining a European reputation and influence. But his hostility to the Revolution went beyond that of most of his party and in particular was challenged by Fox. Burke’s long friendship with Fox came to a dramatic end in a parliamentary debate (May 1791). Ultimately the majority of the party passed with Burke into support of William Pitt’s government. In 1794, at the conclusion of Hastings’ impeachment, Burke retired from Parliament. His last years were clouded by the death of his only son, on whom his political ambitions had come to centre. He continued to write, defending himself from his critics, deploring the condition of Ireland, and opposing any recognition of the French government (notably in “Three Letters Addressed to a Member of the Present Parliament on the Proposals for Peace, with the Regicide Directory of France” [1796–97]).

Learn More!

Edmund Burke

QUICK FACTS

Burke, Edmund

View Media Page

BORN

January 12, 1729?

Dublin, Ireland

DIED

July 9, 1797

Beaconsfield, England

SUBJECTS OF STUDY

American colonies

Burke’s Thought And Influence

Burke’s writings on France, though the most profound of his works, cannot be read as a complete statement of his views on politics. Burke, in fact, never gave a systematic exposition of his fundamental beliefs but appealed to them always in relation to specific issues. But it is possible to regard his writings as an integrated whole in terms of the constant principles underlying his practical positions.

These principles are, in essence, an exploration of the concept of “nature,” or “natural law.” Burke conceives the emotional and spiritual life of man as a harmony within the larger order of the universe. Natural impulse, that is, contains within itself self-restraint and self-criticism; the moral and spiritual life is continuous with it, generated from it and essentially sympathetic to it. It follows that society and state make possible the full realization of human potentiality, embody a common good, and represent a tacit or explicit agreement on norms and ends. The political community acts ideally as a unity.

This interpretation of nature and the natural order implies deep respect for the historical process and the usages and social achievements built up over time. Therefore, social change is not merely possible but also inevitable and desirable. But the scope and the role of thought operating as a reforming instrument on society as a whole is limited. It should act under the promptings of specific tensions or specific possibilities, in close union with the detailed process of change, rather than in large speculative schemes involving extensive interference with the stable, habitual life of society. Also, it ought not to place excessive emphasis on some ends at the expense of others; in particular, it should not give rein to a moral idealism (as in the French Revolution) that sets itself in radical opposition to the existing order. Such attempts cut across the natural processes of social development, initiating uncontrollable forces or provoking a dialectical reaction of excluded factors. Burke’s hope, in effect, is not a realization of particular ends, such as the “liberty” and “equality” of the French Revolution, but an intensification and reconciliation of the multifarious elements of the good life that community exists to forward.

00:01

02:08

In his own day, Burke’s writings on France were an important inspiration to German and French counterrevolutionary thought. His influence in England has been more diffuse, more balanced, and more durable. He stands as the original exponent of long-lived constitutional conventions, the idea of party, and the role of the member of Parliament as free representative, not delegate. More generally, his remains the most persuasive statement of certain inarticulate political and social principles long and widely held in England: the validity of status and hierarchy and the limited role of politics in the life of society.

Charles William Parkin

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

*** ***

https://www.britannica.com/biography/Edmund-Burke-British-philosopher-and-statesman

*** ***

Assinar:

Postar comentários (Atom)

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário