I.L. PERETZ

(1851-1915 | Polônia)

Foi há apenas um

século e meio

aproximadamente, durante o Império Russo, que os judeus mudaram do

hebreu para o iídiche; a base da cultura judaica é a tradição religiosa. O pai

da moderna literatura iídiche, este advogado polonês que viveu em Varsóvia, já

esteve presente em Os Cem Melhores Contos de Humor. .. O massacre do gueto de

Praga originou a lenda do Golem, que resultou num romance de Maurice Meyerling

e neste curto e contundente conto de Peretz, em que o horror histórico e o

sobrenatural místico se encontram.

Quando o gueto de Praga estava

sendo atacado, e estavam a ponto de estuprar as mulheres, queimar as crianças e

cortar em pedaços quem encontrassem pela frente; quando parecia que o fim havia

de fato chegado, o grande Rabi Loeb colocou seu Gemarsh de lado, foi para a

rua, parou diante de um monte de lama na frente da casa do professor e moldou

com ela uma imagem de barro. Ele soprou no nariz do golem - e pôs-se a

massageá-lo; em seguida sussurrou o Nome nos seus ouvidos, e assim nosso golem

saiu do gueto. O rabino voltou à Casa de Oração e o golem jogou-se sobre nossos

inimigos, batendo neles como que a chicotadas. Homens caíam por todos os lados.

Praga estava coalhada de

cadáveres. Isto durou, assim dizem, toda quarta e quinta-feira. Agora já

estamos na sexta-feira, o relógio marca 12 horas, e o golem continua ocupado

com seu trabalho.

"Rabi", gritou o líder

do gueto, "o golem está transformando Praga numa grande carnificina! Não

haverá um gentio vivo para acender as velas do Sabá ou para cuidar das lâmpadas

do Sabá".

Uma vez mais o rabino deixou seus

estudos de lado. Foi até o altar e começou a cantar o salmo "Uma canção do

Sabá".

O golem cessou sua carnificina.

Retornou ao gueto, entrou na Casa de Oração e pôs-se diante do rabino. E

novamente o rabino soprou nos seus ouvidos. Os olhos do golem se fecharam, a

alma que o habitara esvaiu-se e ele voltou a ser um golem de barro.

Deste dia em diante o golem

permanece escondido no sótão da sinagoga, coberto por uma teia que vai de uma

parede a outra. Nenhuma criatura viva pode olhar para ele, principalmente mulheres

grávidas. Ninguém pode tocar na teia, pois quem quer que seja que a toque,

morre. Nem mesmo os mais velhos se lembram sequer do golem, embora o sábio Zvi,

neto do grande Rabi Loeb, tenha levantado o seguinte problema: pode tal golem

ser considerado parte da congregação de fiéis, ou não?

O golem, vejam vocês, não foi

esquecido. Ainda continua lá! Mas o Nome através do qual ele pode ser chamado à

vida num dia que isto se fizer necessário, o Nome, este desapareceu. E a teia

só faz crescer, e ninguém pode tocá-Ia.

O que podemos nós fazer?

Tradução de Flávio Moreira da Costa

Tradução de Flávio Moreira da Costa

I.L. Peretz

POLISH-JEWISH

WRITER

WRITTEN BY:

The Editors of Encyclopaedia Britannica

See Article

History

Alternative

Titles: Isaac Löb Peretz, Isaac Leib Peretz, Isaac Loeb Peretz, Yitskhak

Leybush Perets

I.L. Peretz, in full Isaac Leib Peretz, also

spelled Yitskhak Leybush Perets, Leib also spelled Loeb or Löb,

(born May 18, 1852, Zamość, Poland, Russian Empire—died April 3,

1915, Warsaw), prolific writer of poems, short stories, drama,

humorous sketches, and satire who was instrumental in raising the

standard of Yiddish literature to a high level.

Peretz began

writing in Hebrew but soon turned to Yiddish. For his tales, he drew material

from the lives of impoverished Jews of eastern Europe. Critical of their

humility and resignation, he urged them to consider their temporal needs while

retaining the spiritual grandeur for which he esteemed them. Influenced

by Polish Neoromantic and Symbolist writings, Peretz lent new expressive force

to the Yiddish language in numerous stories collected in such volumes

as Bakante bilder (1890; “Familiar Scenes”), Khasidish (1907;

“Hasidic”), and Folkstimlekhe geshikhtn (1908; “Folktales”). In his drama Die goldene keyt (1909;

“The Golden Chain”), Peretz stressed the timeless chain of Jewish culture.

To encourage Jews toward a wider knowledge of secular subjects,

Peretz for several years wrote articles on physics, chemistry, economics, and

other subjects for Di yudishe bibliotek(1891–95; “The Jewish Library”),

which he also edited. Among

his other nonfictional works are Bilder fun a provints-rayze (1891;

“Scenes from a Journey Through the Provinces”), about Polish small-town life,

and Mayne zikhroynes (1913–14; “My Memoirs”).

00:0002:38

Peretz

effectively ushered Yiddish literature into the modern era

by exposing it to contemporary trends in western European art and literature.

In his stories he viewed Hasidic material obliquely from the standpoint of a

secular literary intellect, and with this unique perspective the stories became

the vehicle for an elegiac contemplation of traditional Jewish values.

Facts

Matter. Support the truth and unlock all of Britannica’s

content.Start Your Free Trial Today

The Peretz

home in Warsaw was a gathering place for young

Jewish writers, who called him the “father of modern Yiddish literature.” During

the last 10 years of his life, Peretz became the recognized leader of the

Yiddishist movement, whose aim—in opposition to the Zionists—was to create a

complete cultural and national life for Jewry within the Diaspora with

Yiddish as its language. He

played an important moderating role as deputy chairman at the Yiddish

Conference that assembled in 1908 at Czernowitz, Austria-Hungary (now

Chernivtsi, Ukraine), to promote the status of the language and its culture.

This article was most recently revised and updated

by Amy Tikkanen, Corrections Manager.

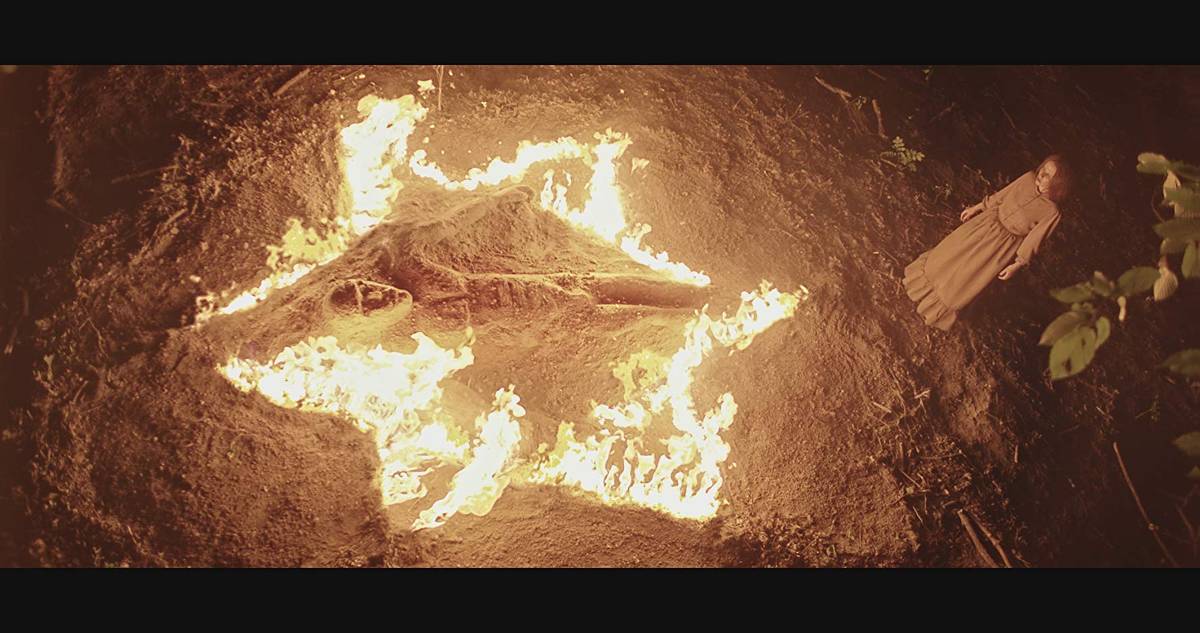

'A Lenda de Golem' é terror que foge

do modelo tradicional

Longa

israelense exige imersão num mundo denso e perturbador

Cena do longa 'A Lenda de Golem' – Divulgação

Referências

https://www.britannica.com/biography/I-L-Peretz

https://f.i.uol.com.br/fotografia/2019/06/12/15603815505d01886eef006_1560381550_3x2_xl.jpg

https://youtu.be/F3DVdwbrjvc

https://www1.folha.uol.com.br/ilustrada/2019/06/a-lenda-de-golem-e-terror-que-foge-do-modelo-tradicional.shtml

Nenhum comentário:

Postar um comentário